Behind Dexter Reed’s Police Killing, a Surge in Traffic Stops on Chicago’s West Side

The police district where Reed was pulled over has the most traffic stops in Chicago. Here’s why activists say that matters.

Pascal Sabino | April 15, 2024

Bolts, a nonprofit journal that covers voting rights and criminal justice in local governments, collaborated with Block Club Chicago, a nonprofit newsroom focused on Chicago's neighbourhoods, to publish this piece.

The incident began as a traffic stop for a suspected seatbelt infraction. In seconds, it turned into a lethal clash.

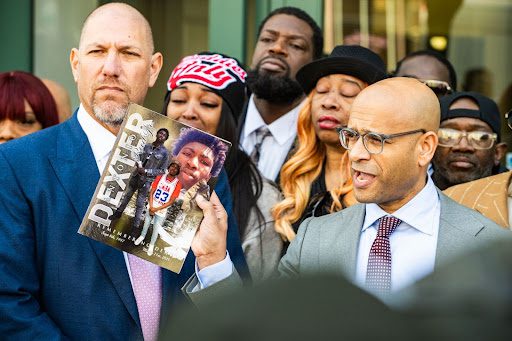

Family members and activists have demanded to know why Dexter Reed, 26, was stopped during a routine traffic stop, how one officer was hurt, and why police opened fire on nearly 100 shots in a residential neighbourhood after body cam footage of the incident was made public.

The traffic stop is a part of a pattern that campaigners claim may violate people's rights and has been targeting Black neighbourhoods more frequently in recent years. "The new stop-and-frisk" has been used to describe the traffic stops.

Additionally, they have been especially hostile on the West Side of the city, where Reed was stopped and slain. For years, activists have cautioned that routine road checkpoints may lead to tense situations.

According to a Block Club Chicago examination of police data, the Harrison (11th) Police area—where Reed was pulled over—actually has more police stops than any other area in the city. Most of those stops result in nothing more than parking penalties.

Despite making up only 3 percent of the city of Chicago's total population, that district accounted for one-tenth of all traffic stops—averaging over 154 stops every day—according to a report by Impact for Equity. The survey states that 96% of the district's residents identify as Black or Latino.

According to Impact for Equity staff attorney Amy Thompson, "the strategy ultimately creates a dangerous situation for everyone rather than contributing to any improvement of public safety in Chicago." "Pretextual stops create danger rather than identify it."

In her opinion, Reed's arrest serves as an example of that risk. For failing to use a seat belt, five plainclothes officers raced outside. It was obviously an attempt to look for criminal activity, she claimed.

The monitoring body in Chicago that looks into shooting incidents involving police, the Civilian Office of Police Accountability, expressed reservations about the justification provided by the officers for stopping Reed. Chief administrator Andrea Kersten issued a letter to Police Supt. Larry Snelling that was received through a Freedom of Information Act request. In it, she expressed uncertainty about how cops could have observed that Reed was not wearing a seat belt given their locations and the fact that Reed's SUV had tinted windows.

The cops engaged in the deadly shooting were under investigation for multiple earlier traffic stops, which drivers claimed were unjustified, according to recently disclosed papers.

Last year, Police Superintendent Larry Snelling—who rose to the position of top cop in Chicago—said there was an issue with the quantity of traffic stops. He has promised to cut back on traffic stops, going against the policies of the previous administration. In addition, he promised to regularly train police to make sure they only act on "reasonable articulable suspicion or probable cause," as he stated to the community the day before video of Reed's murder was made public.

"Because of the way this plan is being implemented, some have been raising alarms that the dramatic increase in traffic stops might result in more violent encounters. The Illinois ACLU's Ed Yohnka stated, "We anticipated we would have some tragedy like this occur as a result of these stops because they have become so routine and useless. "The stops happen in this way, with guns drawn and things escalating right away."How stops surged after Chicago funneled more cops to traffic stops

After a 2015 ACLU analysis revealed that stop-and-frisk encounters were usually unfounded, targeted Black and Latino Chicagoans, and habitually violated people's rights, traffic stops in Black neighbourhoods increased. Chicago police started using traffic stops when the city decided to change the procedure, according to Yohnka.

The Illinois Traffic and Pedestrian Stop Study shows that the number of traffic stops Chicago Police reported to state watchdogs increased from less than 100,000 in 2015 to around 600,000 in 2019. According to the Impact for Equity study, Chicago police recorded their second-highest number of stops in two decades in 2023 after a decline in documented stops during the early years of the pandemic. According to the state data, black drivers are pulled over up to seven times more frequently than white vehicles. While police stop a disproportionate number of drivers in Black neighbourhoods, there are minimal traffic stops in districts with a high concentration of police officers.

However, the study significantly underreports traffic stops by Chicago police. According to a Block Club study, the department failed to disclose to the state hundreds of thousands of traffic stops each year, in violation of a transparency statute designed to combat racial bias tendencies in police encounters.

According to a Block Club research, Chicago police stop and jail thousands more Black drivers than they disclose to oversight agencies because they rely largely on these contacts to look for contraband like illegal firearms and drugs. According to research by Block Club and Injustice Watch, police make millions of stops, but they only find firearms in less than 150 of those cases.

"It is evident that traffic safety has nothing to do with this type of stop. It ultimately comes down to looking for narcotics and firearms, according to Yohnka. "You look at that situation much differently than someone who rolled through a stop sign if your expectation is to try and find a weapon."

Chicago police have funneled resources and manpower supposedly earmarked for other public safety strategies to make more traffic stops and scale up gun arrests, Bolts and Block Club have found.

The signature project of David Brown, Snelling’s predecessor, was a community policing unit purportedly launched to build trust between South and West Side residents and police, solve local problems and tackle crime at its root. By 2021, it was the largest unit in the department with over 800 officers.

But an analysis of dispatch records by Bolts showed those officers rarely did those positive community engagement activities. Instead, they were deployed primarily on the South and West sides as a roving strike team and the central enforcer of the growing traffic stop program. The community policing team stopped and searched more drivers than any other police unit, amounting to nearly one-third of the mountain of traffic stops in 2021, data shows.

The community team was dismantled amid outcry from watchdogs and legal turmoil from drivers and officers who complained of an illegal quota system that discriminated against Black Chicagoans.

An ongoing class action lawsuit filed by Black and Latino drivers and the ACLU alleges the traffic stop strategy—and Brown’s community team in particular—flooded Black neighborhoods with traffic stops as a pretext to search drivers without their consent. The complaint references emails sent by then-Deputy Superintendent Ernest Cato III that ordered commanders to “utilize traffic stops to address violence.”

A former lieutenant on the community team sued the city in 2021, claiming leadership retaliated against him for refusing to require officers under his command to conduct at least 10 stops daily. Though the community team was disbanded, Snelling reinstated it under a new name.

“Every officer in those units is not one that’s in the community, talking to neighbors and trying to find solutions,” Yohnka said. “Our clients described traffic stops where officers approach the car with their hand on their gun. People are being singled out and targeted for their race. It points out the danger of these stops, the inefficiency of the stops and the tragedy of the situation.”

Officers who are supposed to respond to 911 calls have also been steered toward traffic stops, a Block Club investigation found.

Hundreds of officers each day are assigned to rapid response duty, answering top-priority 911 calls and reducing long wait times that have become a pressing concern for many communities, according to police directives. It is supposed to allow beat officers to stay on their local patrols and build community relationships rather than respond to emergency calls.

But dispatch data shows rapid response officers rarely handle 911 calls. Instead, the majority of those officers are dedicated to traffic stops, the data shows.

“That’s a lot of manpower,” community organizer Arewa Winters said. “While we have all these issues going on everywhere, and you’re pulling people over with no good outcomes. Is that a practical use of manpower? Could you be somewhere else doing something else?”

A promise to reduce traffic stops: ‘We have to unlearn old things’

Snelling, the city’s first superintendent chosen under a new community oversight commission, has broken from past leadership by promising to address the harms caused by the mass use of traffic stops.

Former Supt. Brown denied the existence of racially discriminatory stops and quotas and rejected evidence that stops were used to fish for gun possession cases.

At an April community hearing, Snelling acknowledged how traffic stops are part of the department’s strategy for dealing with guns, touting the department has scaled back on traffic stops while still increasing gun arrests. Snelling plans to continue to reduce traffic stops by training officers on different tactics, he said.

“We have to train the officers out of that and bring them into something new,” Snelling said. “In order to get them to learn new things, we have to have them unlearn the old things.”

Snelling said Chicago police have conducted 46,000 fewer stops in 2024 compared to the first quarter of last year. Police spokesperson Thomas Ahern declined to share a source for how the department tracked that reduction in stops, saying the statistic came from “computer data.”

To address the long-term issues with traffic stops, Snelling committed to bringing traffic stops under the supervision of the federal consent decree so the reductions “will be long lasting after I am gone,” he said.

But many are skeptical and urge the superintendent to take more immediate action. Only 6 percent of the requirements from the consent decree have been met in the five years since it took effect, according to a recent report.

“Whether or not Snelling views traffic stops differently, in order for community to have clarity on what their interactions with law enforcement will be, and even so police has clarity on what they can and cannot do, there needs to be a formal policy on these pretextual stops,” said Thompson of Impact for Equity.

When the goal is to investigate unrelated crime, officers are motivated to escalate a traffic stop to search for contraband, not deescalate the situation, Winters said. The tactic widely used in Black neighborhoods thrusts hundreds of thousands of Chicagoans each day into a high-risk situation that could turn lethal at any moment.

Investigators concluded Reed shot at officers first. But the focus on who fired first distracts from the bigger picture, Winters said: Neither the officers nor Reed were in a potentially deadly situation until police pulled Reed over.

“The conversation needs to begin with what the police started with and how they approached that young man.”

It is reminiscent of when officers killed Philando Castile during a traffic stop near Minneapolis in 2016, Winters said. Officers used a broken taillight as a pretext to stop Castile and investigate him for an unrelated armed robbery nearby, an investigation showed. Within a minute of the encounter, officers fired at Castile while his girlfriend and her 4-year-old child were in the car.

That same year, Winters’ nephew Pierre Loury was killed after officers pulled over a car he was in to investigate a shooting earlier that day. After the 16-year-old tried to run away, an officer shot Loury after the teen climbed a fence.

“I know so many other families who have lost loved ones to police. We’re retraumatized, we’re frustrated, we’re angry, we’re hurt,” Winters said. “It’s truly overwhelming. But at the same time, we have to fight. We have to push back on the narratives that they try to spin.”

No comments:

Post a Comment